Hey GameMakers!

As projects get bigger and more complex, we often find ourselves wanting to add the same features and functionality of one object to many other objects. Maybe this object is movable, that object is collidable. This object can be paused, that object is depth sorted.

Sometimes these elements can be less about what the object’s core behavior is, but rather tiny additional features that you may want an object to support. Like an object who can “flash” when damaged or when interacted with in some way, or an object who can read input from the player.

Update 8 / 17 / 2022 Found an issue with the flash hook logic. Updated the tutorial accordingly.

Parenting

Our first instinct as Gamemaker developers when encountering an issue like this is to use parenting. Using parenting we build long chains of object types that inherit from one another, and at the end we get these very complex leaf nodes that are a combination of everyone that came before them. You might end up with a hierarchy that looks like this:

objDepthSorted ➡ objMovable ➡ objPausable ➡ objActor ➡ objNPC ➡ objManGuyMcDude

And this works great. Manguy McDude is an NPC / Actor who I need to be able to move and pause and display depth sorted against other depth sorted objects. His events can all inherit from every parent object all the way up the chain. There are some pros and cons to this approach.

One pro is that objManGuyMcDude is not just objManGuyMcDude. He is also objNPC and objPausable and any other parents all the way up the chain above him. There are several built-in functions in GM that will accept an object index and will operate on all instances of that object or any instances of ANY child instances for the given object. Want to pause all objects?

1

with(objPausable) paused = true

…and objManGuyMcDude will also get paused since he is an objPausable child. This is really handy. You’ve likely done this at least once with wall objects; one parent: “objWall” and then a bunch of different objects with different sprites and masks of different shapes and sizes. Then your collision check is just:

1

if(place_meeting(x, y, objWall)) { }

Much cleaner than trying to chain multiple place meetings together for all the different collidable objects.

A possible drawback of this approach is that it’s all or nothing. For each event of every object in the chain you either call event_inherited() to get all of the functionality of the parent object or you don’t call it and get none of the functionality of the parent or the parent above that one. You could try setting some flags and optionally call event_inherited in certain situations but that’s likely to get complicated very quickly.

Even if you do work out a good way to optionally run your event_inherited, it’s still always going to run in the same order with no way to weave other code in between as needed on the child object. It’s very rigid.

What if you wanted to mix and match parents from the chain? Now things really begin to break down. Need an NPC that isn’t pausable? Doesn’t move? Isn’t depth sorted? Now you have to create a new branch of parent child relationships to support that specific case. Your tree gets more complicated.

Furthermore, any changes to any part of a parent object can have undesired effects at any point down the chain; even when the child object doesn’t really want or need those specific features the parent implements. It’s a precarious Jenga tower and with each change you run the risk of making it more and more unstable.

Is parenting bad? Should it be avoided at all times?

ABSOLUTELY NOT!

Parenting has a place in nearly every project. What I’m proposing in this article is an alternative way of providing features and functionality to many different objects that doesn’t rely on a long, linear chain of inheritance. Let’s talk about how.

The Hook Pattern

With the release of Gamemaker Studio 2.3 we got Structs and Functions. These were a game changer for how we built our objects and organized our projects; so many new possibilities were made available to us. One of the most exciting things is we could now draw even more inspiration from what developers were doing in other programming languages who share similar features. In the case of the hook pattern, inspiration was drawn from Javascript; specifically the ReactJS library.

Before React implemented hooks, they had a similar problem: components could contain other components that could contain other components, etc, etc. And if you wanted to get some properties or functions to a component down the chain, it would need to be passed into each parent and then handed down to each child manually. It was a nightmare.

With hooks, any child could simply say “hey, I need this” in its definition and it didn’t matter who was above or below them; they just had access to it to use as they saw fit. With structs and functions we can do something similar.

Component Pattern The hook pattern is really just an implementation of the component pattern. Read about it here.

The pattern itself is pretty simple: build a struct that holds all of the properties and functions needed for a specific feature or function. Build a function or constructor that creates an instance of that struct for an object. Use that struct throughout the object’s various events to gain access to the same functionality and necessary properties.

Now you can mix and match as many different features for any object in your project.

But the best way to learn is to do! With that in mind, let’s build our own hook!

A Simple Flash

Being able to flash a sprite a solid color is a pretty common feature in games. Almost anything in your game could flash for any reason: the player when taking damage, an item when sitting on the ground, a door when unlocked. If it shows up in your game, you may want to flash it to draw your player’s attention.

Can you imagine building an objFlash parent? What it might look like and how it would fit in your inheritance chain if you wanted to use parenting to pass that functionality down to other objects?

I can. I’ve done it before. It wasn’t very fun!

Instead, let’s write and implement a hook that we can use in any object to flash its sprite.

Start by creating a new object. Give it a sprite and drop it in your room.

Let’s think about all the things we need to make this feature work. Imagine it’s already built. How would you want to interact with it?

You’d need some way to “start” a flash. Something like start_flash() that would kick off the effect. You could pass some properties in there like what color you want the flash to be, or how long the flash should last.

Then we’d need some way to draw the flashed version of the sprite. A draw_flash() function that we can overlay on our default drawing.

Finally we’d need to make sure that we had all the variables responsible for controlling the drawing and the animation available to us. The color, the current alpha, the timer remaining on the flash, etc.

Open the create event of our object so we block out a struct that has a place for all of that.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

flash = {

color: c_white,

alpha: 1,

flashDec: 0, //how much we reduce the flash each step.

start: function(){},

draw: function(){}

}

NOTE: Notice that I stored the struct in a variable I called flash. It’s important to keep this in mind when naming properties and functions in your hook. We don’t want to call our color property flashColor or our start function flashStart. We’ll already be using the flash variable when we access them. It would be redundant if we had to type flash again like this: flash.flashColor. Keep your names in the context of a single flash instance.

Being able to “start” a flash doesn’t matter if we can’t see it. Let’s build the draw function first.

First, how do we draw a sprite as a solid color? “Shaders” may be an answer you’ve heard thrown around to answer this question. And while that is certainly an option, technically we can do it with the “default shader” that GM is always drawing your game with! Even if you aren’t using a shader, you are. We can exploit the fog feature of this shader to force something to be drawn with a solid color. Let’s start with that:

1

2

3

4

5

draw: function(){

gpu_set_fog(true,color,-16000,16000);

draw_sprite_ext(sprite_index, image_index, x, y, image_xscale, image_yscale, image_angle, image_blend, alpha);

gpu_set_fog(false,0,0,0);

}

Add a draw event to your object and add this code:

1

2

draw_self()

flash.draw();

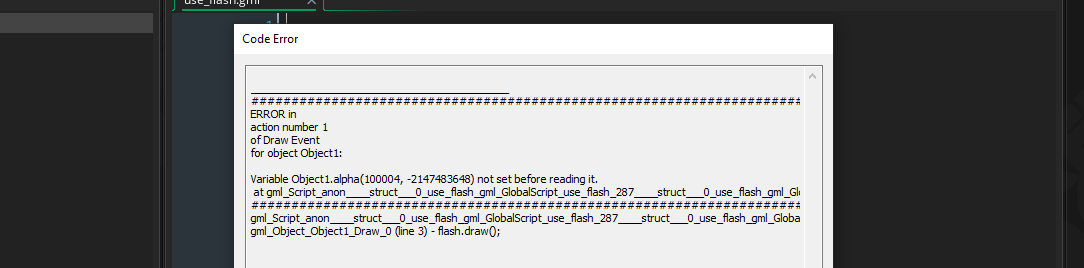

Run the game.

Uh oh. What happened? Why didn’t this work?

This function is defined within the context of our flash struct. The flash struct doesn’t have a sprite_index, image_xscale, image_blend, or any of the other “built in” instance variables we know and love. So we need to draw this sprite in another context. But which context to draw it in?

When using the hook pattern, it can sometimes be helpful to know which instance you’ve “attached” the hook to. As such, let’s add a new property to our flash struct to keep track of that.

1

2

3

4

5

flash = {

owner: id,

color: c_white,

//...etc...

}

We’ll keep track of our “owner” id, and we can use that whenever we need to reference variables hosted in the instance that originally used the hook.

Now back in the draw function, we’ll just use with(owner) before we draw the sprite. This will draw the sprite using all the owner’s variables. That causes one further issue: our owner doesn’t know what alpha is; that’s a property defined as part of our struct. So we need to use other to change our context back to the struct, and find the alpha:

1

2

with(owner)

draw_sprite_ext(sprite_index, image_index, x, y, image_xscale, image_yscale, image_angle, image_blend, other.alpha);

An alternative to this is to allow draw() to accept all the arguments you would normally use when calling draw_sprite_ext() - besides alpha since that will be controlled by the flash itself. But that makes using the flash a bit more tedious, so I’m opting for the first option. Do what’s best for you and your project.

So with that fix that uses with(owner) and other.alpha, we can run the game.

There we go. Solid color sprite. To prove that our alpha and color properties are being respected, go into the flash struct and change the alpha from 1 to .5 and the color from c_white to c_red. Run again and you should see the sprite covered with a red tint.

Now that we can see our “flash” -despite it not being very flashy yet- we can write our function that will start a flash.

1

2

3

4

start: function(_length = 10) {

alpha = 1;

flashDec = 1 / _length;

},

This function accepts an argument that controls how long the flash will last in steps. The default is 10 steps. We divide 1 by the number of steps to give us the amount we need to reduce alpha each step to reach 0 in that number of steps; in this example we reduce it by .1 every step. We also set alpha to 1 since we always want our flash to be solid on the first frame.

Add a step event to your object and let’s start a flash when we hit the spacebar.

1

if(keyboard_check_pressed(vk_space)) flash.start()

Run your game and hit spacebar.

Not terribly impressive. It just went from partially red to a solid red. That’s because we aren’t actually using our flashDec variable yet. Let’s go back to the draw function and reduce our alpha every time we draw.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

draw: function(){

gpu_set_fog(true,color,-16000,16000);

with(owner)

draw_sprite_ext(sprite_index, image_index, x, y, image_xscale, image_yscale, image_angle, image_blend, other.alpha);

gpu_set_fog(false,0,0,0);

alpha -= flashDec;

}

After we reset the fog, just reduce our alpha property by flashDec.

While we are here, let’s set the default alpha to 0, and set our color back to c_white. Run again and press spacebar.

There we go! Now every time you press spacebar, your character will flash white! Try passing in a different length of time when you call start()!

Let’s make this just a bit cooler. Let’s allow you to pass a color into start to change the color of the flash.

1

2

3

4

5

start: function(_color, _length = 10) {

alpha = 1;

color = _color;

flashDec = 1 / _length;

},

Back in the step event, let’s call it with a random color.

1

if(keyboard_check_pressed(vk_space)) flash.start(irandom(c_white))

Why c_white? c_white is the “highest” color since it is 3 bytes all at max value: 255, 255, 255. So picking a random number between 0 (black) and white will give you any possible color!

Spam that spacebar and enjoy the show!

Creating your Hook

We’ve created this handy struct, but it still belongs solely to this one object. To make this a “true hook” we need to make it reusable. Now that you’ve already built it in this manner, this is SUPER easy.

Go to your create event, cut it, and just build a new function that returns this structure.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

///@func use_flash()

function use_flash(){

return {

owner: id,

color: c_white,

alpha: 0,

flashDec: 0, //how much we reduce the flash each step.

start: function(_color, _length = 10) {

alpha = 1;

color = _color;

flashDec = 1 / _length;

},

draw: function(){

gpu_set_fog(true,color,-16000,16000);

with(owner)

draw_sprite_ext(sprite_index, image_index, x, y, image_xscale, image_yscale, image_angle, image_blend, other.alpha);

gpu_set_fog(false,0,0,0);

alpha -= flashDec;

}

}

}

Why “use_”? This is a naming convention established back in ReactJS. All hooks are named with the “use_” prefix. I like the convention, so I stuck with it. You can name yours whatever you want, obviously.

Back in our create event, we just call this function and store the return in our flash variable.

1

flash = use_flash();

We now have a flash hook we can use in any object for any reason regardless of who their parent is! Additionally any of their children can use the flash variable if they have inherited the create event of that object.

You could make this hook a constructor that you call using the new keyword and it really doesn’t change anything. It’s up to you how you want to do it. As long as you are returning a struct that has everything you need for the feature or functionality, you’ve built a hook!

Summary

I’ve begun adopting this pattern all over the place. My recently updated assets: TDMC, TrueState, and Scripture all follow this pattern. TrueState demonstrates how you can have multiple copies of the same hook in a single object to perform different, parallel tasks. My upcoming input asset also follows this pattern. I expect all my assets or any updates to my current assets to follow this pattern for the foreseeable future.

Let me know if you have any questions or comments down below or on twitter. If you like this pattern and end up using it yourself, ping me on twitter; I’d love to see what you built.

Thanks for reading!

Now go make something awesome!